How to think about debt

Debt is an instrument and not a taboo. Used rightly, it allows you to take advantage of opportunities you may otherwise miss; used wrongly, you may hurt yourself.

Debt has been around for at least as long as the concept of money. Various cultures and religions have tried to condemn it or ban it throughout history by conflating it with usury, yet it prevails everywhere around us. Debt is Lindy1. It is not going away anytime soon.

Many people associate a highly negative connotation with debt, consider it a poisoned chalice and refuse to engage with the idea. Yet debt is a highly effective tool like a knife or fire. Used in the right manner it can be of benefit. Use it wrongly and you may end up hurting yourself. In this post, I’ll share my perspective on debt, where it can be useful for building wealth, where it’s not useful and where the distinction isn’t that clear-cut.

A few disclaimers before we dive into the discussion of the usefulness of debt.

When talking about debt, we’ll strictly refer to monetary debt. Where you borrow a principal sum of money in the present with the promise to repay the principal and some cost in the future. We won’t be speaking of ‘debt of gratitude2’ or charitable debt3.

You can refer to the cost that you repay in addition to the principal by any of the popular terms such as interest or rental or fee or margin. In almost all commercial transactions there’s always a cost to borrowing money. Even lending products labelled as interest-free aren’t always free. There’s almost always some fee added in the fine-print. If you borrow $100 today and repay any amount more than $100 in the future, you are paying the cost of borrowing.

I will not be talking about any religious aspects of debt. I don’t feel qualified to talk about that matter. If you feel as a matter of faith that engaging with debt is forbidden under your religious views; I respect that and I won’t argue against that.

I would however draw a distinction between debt and usury. In a normal debt transaction, the lender expends some effort to assess the borrower’s ability to pay back and charges a price that is within reasonable bounds of the prevailing market interest rates. In good faith, the lender expects to be paid back at the end of the borrowing period. In predatory lending, the lender often knows that the borrowers may not be able to pay them back. They charge ridiculous fees and costs well beyond reason. The objective often is to trap the borrower in a vicious cycle of debt, to force the debtor to sell their assets at throwaway prices if not outright confiscating them. Predatory lending is more like usury. I do not condone usury.

Debt is useful when you can earn a monetary return from utilizing debt higher than the cost of that debt. This concept can be better explained with the help of an example.

Say you decide to start a lemonade-stand business using your savings. After buying material for the stall, you only have $100 to buy inventory each day. Every morning you buy $100 worth of inventory of lemons, cups, ice and sugar, and then use this inventory to make and sell lemonade during the day. You make a 10% profit margin on selling lemonade. Within a few days of doing business, you realize that with $100 worth of starting inventory, you run out by noon and miss half a day's worth of sales. Customers aren’t happy that you run out of stock in the middle of the day.

Your neighbour offers to lend you an additional $100 every morning if you could return $102 at the end of the day. That’s a 2% daily interest rate translating to 700%+ annualized which is generally an extremely high borrowing cost. Yet if you are able to use the borrowed $100 to buy additional inventory and make $10 in additional profits, you are better off by $8 by taking on this debt.

To use another example common in personal life. Say you just graduated college and started a new job. To commute you take a taxi twice each day. With each trip costing $20, 2 trips daily and 22 working days, you’re spending about $880 on taxis every month. You check with your local bank for a car loan and do the calculations to discover that leasing a car + insurance + parking, fuel, maintenance will cost you $600 every month. You’d be saving about $280 every month if you take on the car loan and start driving to work yourself.

Sometimes the benefit is not directly monetary. To use the same commuting example again, say instead of by taxi you commute by bus everyday. Taking the bus takes an additional hour each day compared to a car but costs only $300 a month. If you take on the car loan, you’ll be spending an extra $300 every month but you’ll be saving 22 hours over the month. If you value that extra time you have for your family, friends and leisure activities for more than $13.6 per hour, then the time saved will be worth more than the additional costs of leasing the car.

Sometimes you don’t have a choice. You get into a health emergency and don’t have the funds to pay the insurance excess, or the full bill if you don’t have insurance. Though it’s always best to never be in the position where you may end up in a situation like this by keeping emergency cash reserves. In this unfortunate scenario, if you do have a debt facility available to you, it’s probably better to draw on it. You can have your health restored immediately and then figure out whether it’s better to sell some assets to retire the debt immediately or to gradually pay back the debt with your income.

Banks and financial institutions are most eager to lend to, in order of preference, people they know who have a good track record of taking on debt and paying it back on time i.e. a good credit score; a complete stranger and lastly; people they know have a bad reputation of taking on debt and then not being able to pay back on time.

Even if you have no otherwise productive use for taking on debt, in our modern economies, sometimes it is useful to still take on a little bit of low-cost debt to build your credit score. You can make purchases on your credit card, earn reward points and pay off the bill fully each month. In this way you may not take on additional borrowing costs yet still be able to build credit history with the bank. If you may need a loan or mortgage from the bank in the future, having a good credit history enables you to get more favorable terms from the bank as compared to having no credit history.

If your objective is to build long-term wealth, then taking on debt for personal consumption is one of the worst things you could do. It’s easy to say this, hard to resist all the offers that credit card companies advertise in their savvy marketing, all the temptations to buy from your favorite brands on a Buy Now Pay Later deal.

Upgrading to a bigger house or a fancier car when your current one is just fine by taking on a larger mortgage or car loan is going to push your wealth-building goals further away in time. You will always be paying the bank in interest costs money that could otherwise be invested and allowed to compound over time. We talked a lot about building personal wealth through compounding in the previous posts on personal finance.

You don’t have to live like a pauper in the present. If you do desire a bigger house, luxurious car or fancier vacation, then spend from your savings. Don’t take on debt to finance them or spend money you don’t have on luxuries you don’t need. Winning no short-term status game can give you the long-term fulfillment that comes from freedom earned from your personal wealth.

The usefulness of debt for investing isn’t that clear-cut and requires careful analysis. The most common significant situations being student-loans for investing in a university education for yourself and mortgages to buy your primary home. Other popular schemes include taking on debt to invest in real-estate, equities or other assets.

It’s not easy to financially model these scenarios on a spreadsheet since you’d have to make projections over multiple decades in the future and across a lot of unknowns. Yet the financial modeling exercise is a useful tool to help think long and hard through these scenarios and the trade-offs involved. Let’s consider a few examples.

Student Loans. You’ve just graduated from your local high-school and have offers from two universities. A no-scholarship offer from a prestigious university and a partially funded offer from a regional non-brand university. After accounting for your personal savings and parents’ contributions, going to the prestigious university would require you to take $200,000 in student loans whilst going to the regional university would require $50,000 in student loans. Your third option is to not go to university and start working some trade directly after high-school.

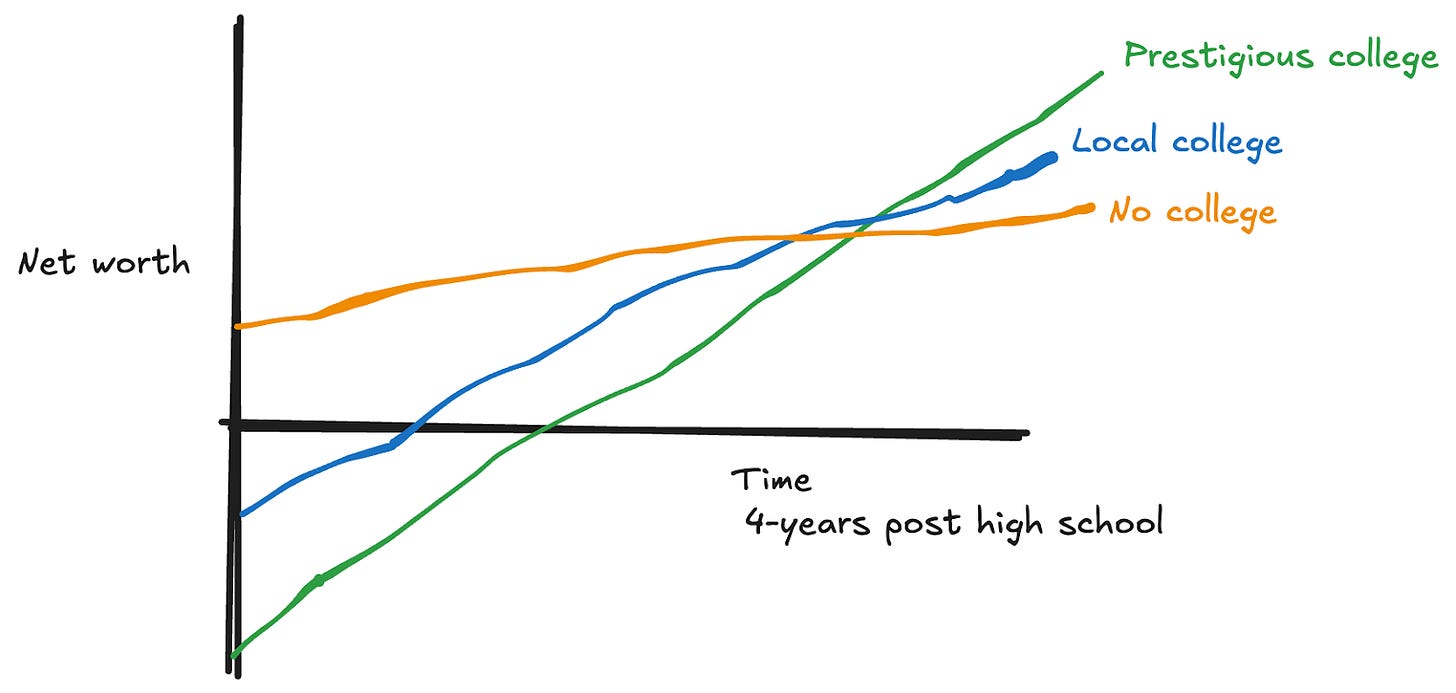

By choosing the prestigious university you’ll graduate deeper in debt but more likely to be employed in a prestigious firm that mostly hires from target schools i.e. prestigious universities. By joining these prestigious firms, you’ll have higher starting salaries with steeper room for growth and larger long-term wealth prospects. By not going to university, you’ll have a higher, positive net worth at the time your peers are coming out of university, but you may be in a job with limited growth. The likely payoff curve from either choice would appear as follows:

What you would choose to study in university should also be a big factor in your analysis. Even at the same prestigious university, different degrees can lead to different incomes post-graduation. Engineering majors generally receive much higher salaries post-graduation than art majors.

If your passion is in the performing arts, you may be better off financially by apprenticing and practicing straight after high school as opposed to taking on a large student loan to do a degree in theatre. A loan that you’ll struggle to pay-off with the low expected salary post-graduation.

If you commit to take on the student loan, you’d also reduce your options or flexibility in the future. You may not want to be in the situation where you took on a large student loan to pursue an engineering degree but then midway through college realize that your true calling is in the theatre. You’d graduate with the same debt load of an engineering student but the earning potential of a performing artist. If you’d want to take a gap year to ‘discover yourself’ you should ideally take it before you take on the student loans. You may not want to have that year after college where you aren’t earning but your student loan debt is compounding.

Buying your first house mortgage. You can’t quantify the satisfaction derived from having your own place to call home, not having to deal with landlords for maintenance and not having the constant fear that your landlord may suddenly increase the rent once your contract comes up for renewal. Many societies like the US value home-ownership, whilst many like Europe find it fine to be renting your house for a long time.

Often it also makes economic sense to buy your house on a mortgage once you can afford the down payment. Your monthly mortgage is often less than the monthly rent plus it also adds to your home equity by gradually paying off the principal loan amount.

Yet there are situations where you can be worse off owning a home on a mortgage versus renting a home.

The switching costs incurred when moving places are much higher when you have to sell and buy a new place versus changing rentals. You pay realtor fees, often 2-3% of property value, twice when selling the old place and buying a new one. Your mortgage may get re-priced when you change properties, So if you bought the first one during a time of low-interest rates, then your interest payments may go up with the new property if interest rates had gone up since then. The housing market may be in a temporary slump and your old house may be less than what you paid for it, or may not have appreciated in as much value as what you had spent on renovations.

With rentals it is much easier to trade down If your income decreases due to losing a high-paying job or one-partner taking a break, as opposed to trading down when you have bought the house on a mortgage.

Therefore, before you commit to purchasing your house on a mortgage, you should be certain that you’d want to be living in that property for the long-term and that your household income is consistent enough or buffered with adequate savings to be able to continue servicing the mortgage payments for decades.

Taking on debt for investments significantly increases the risk and return of investments; hence why it’s also called leverage. This is due to the simple reason that you’ll have to pay back the exact agreed-upon amount as per the exact schedule regardless of whether your investments face a boom or a bust.

Many people choose to take on debt for investing in stocks, also called buying on margin, or engage in buy-to-let real-estate plans where you hope to pay off a house’s mortgage from the rent earned from tenants and in process build your equity in the property. We previously talked about the risk and return profiles for stocks and real-estate.

There is no clear answer whether you should or should not take on debt for investing. Like most things in life, the answer is “it depends”. What’s critical to realize is that if you plan on using debt for investments, then you should invest a lot more effort in carefully analyzing your investment opportunities and risk profiles and only invest equity that you can afford to lose. If you don’t consider yourself a professional investor in that respective domain, then it’s best to not invest with leverage.

Many people have built fortunes without taking on debt and many people have lost fortunes by taking on too much debt. Many people consider debt a taboo whilst others consider it a panacea to live their dreams4. I don’t intend to prescribe or prohibit debt to you. Rather I hope you now understand it is a commercial instrument in your toolkit, are aware of how to acquire it, when to deploy it and when to keep it sheathed.

PS While I was writing this article, a new startup Basic Capital announced its launch. It’s pitch, as per Bloomberg is:

Its 401(k) and IRA platform offers savers $4 in leverage for every $1 saved.

How timely. If you’d like me to do a subscriber-only financial model breakdown of Basic Capital, let me know in the comments.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindy_effect

That feeling of thankfulness or appreciation when someone does you favor and you feel you owe them a favor back.

When someone lends you money to help you recover from a precarious situation and generally doesn’t expect you to pay them back or there’s no commitment or promise from you to pay them back.

Before the debt repayment turn the dreams into a nightmare

Such a smooth read